In the German hamlet of Neuengamme, a short drive from Hamburg and Geesthacht sits a sobering reminder of man’s inhumanity to man – a concentration camp.

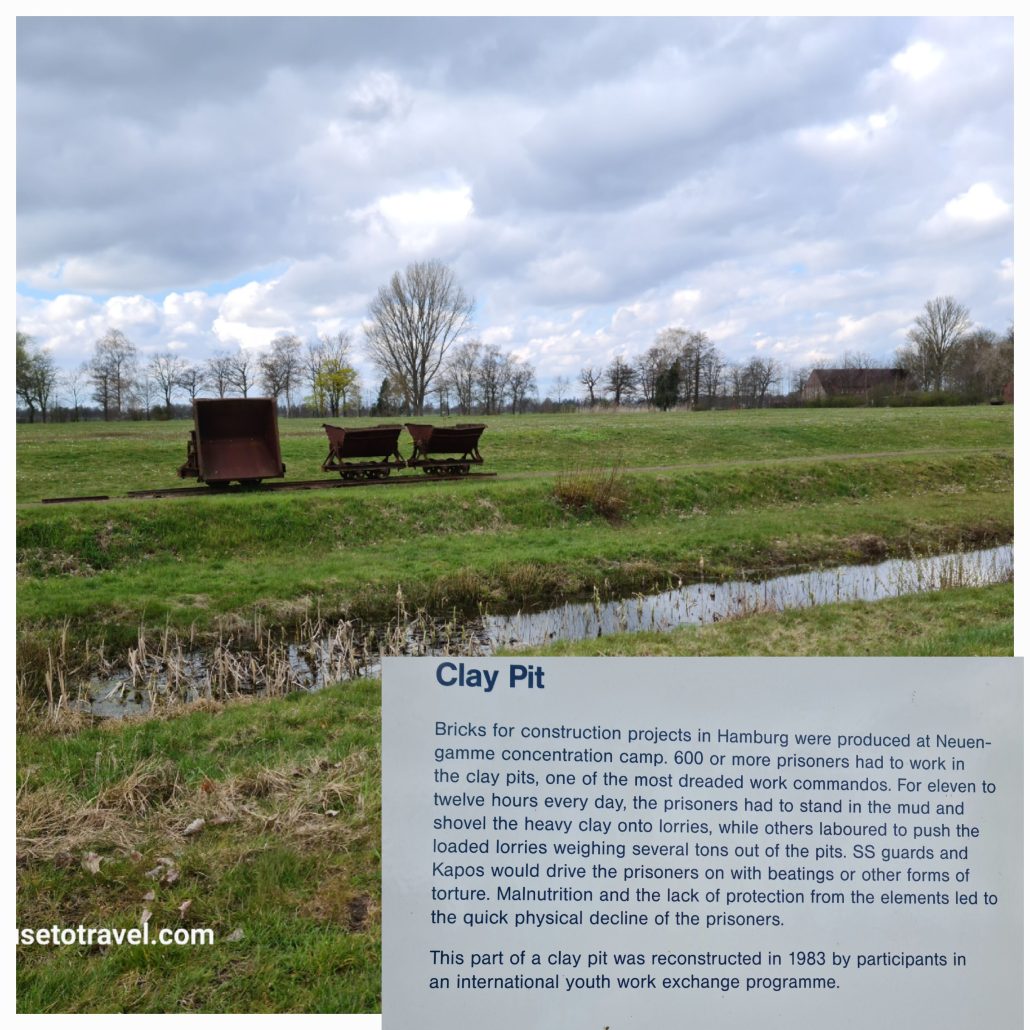

Once a working brick factory, property of the German Earth and Stoneworks, the abandoned site was taken over by the SS who had other ideas of how to use the space.

Neuengamme was to become a satellite camp for the larger Sachsenhausen, some 278 km away. The plan was to put the brick factory back into operation using forced labour, supplied by those who were at odds with the regime. Work began in December 1938. In 1940, the camp became independent and went on to add a further 80 subcamps to its holdings. Later, in 1942, three companies would establish sites in the camp:

The Walther-Werke, based in Zella-Mehlis, established a manufacturing plant for small arms production that deployed around 1,000 prisoners. In April 1942, the Carl Jastram Motorenfabrik built a plant for the production of U-Boat parts, the repair of ship motors and the production of torpedo boats. At the end of 1942, the Deutsche Meß-Apparate GmBH based in Langenhorn, established a plant in Neuengamme to produce fuses for anti-aircraft grenades.

The Holocaust is a blight on human history. The determined attempt to wipe Jews off the face of the earth is beyond horrific. That some people deny this happened beggars belief. We would do well to remember that concentration camps, ones like Neuengamme, were indiscriminate. Anyone who upset the general order was welcome. Dissenters, resistance fighters, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, anyone who didn’t behave as was expected.

From 1939 to 1945, it’s estimated that over 106,000 people (men and women) walked through the gates of Neuengamme. Half of them would not survive.

The death register at Neuengamme indicates that about 40,000 prisoners died in the camp by April 10, 1945. Perhaps as many as 15,000 more died in the camp in the following week and during the course of the evacuation. In all, more than 50,000 prisoners, almost half of all those imprisoned in the camp during its existence, died in Neuengamme concentration camp.

As I walked around the foundations of the barracks where the inmates were held, a thought popped into my head: At least there were no gas chambers. I was so shocked I had to sit down. Was being worked to death better than being gassed? [The phrase ‘extermination through labour’ – ‘Vernichtung durch Arbeit’ in German – was reportedly coined by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, in 1942.] Was I really evaluating atrocities in terms of the lesser of two evils? Had previous visits to camps in Terezín, Czech Republic; Salaspils, Latvia; Auschwitz, Poland; or Dachau, Germany left me cold? Had the atrocities I hear of every single day dulled my senses? I knew I couldn’t empathise but had I run out of sympathy? What was going on?

I thought long and hard about my somewhat academic reaction to the Neuengamme as I walked through the exhibitions. There was a school tour going on that day. Lots of teenagers milled around, checking out the exhibits. I had the sense that it was all going over their heads. The shock factor seemed to be missing. It felt as if, for them, the testimonies on display were simply chapters in a story that was no longer relevant. It was yesterday. Not today. Not tomorrow.

It wasn’t that I wasn’t moved – how could I not be? But there was something I couldn’t quite put my finger on.

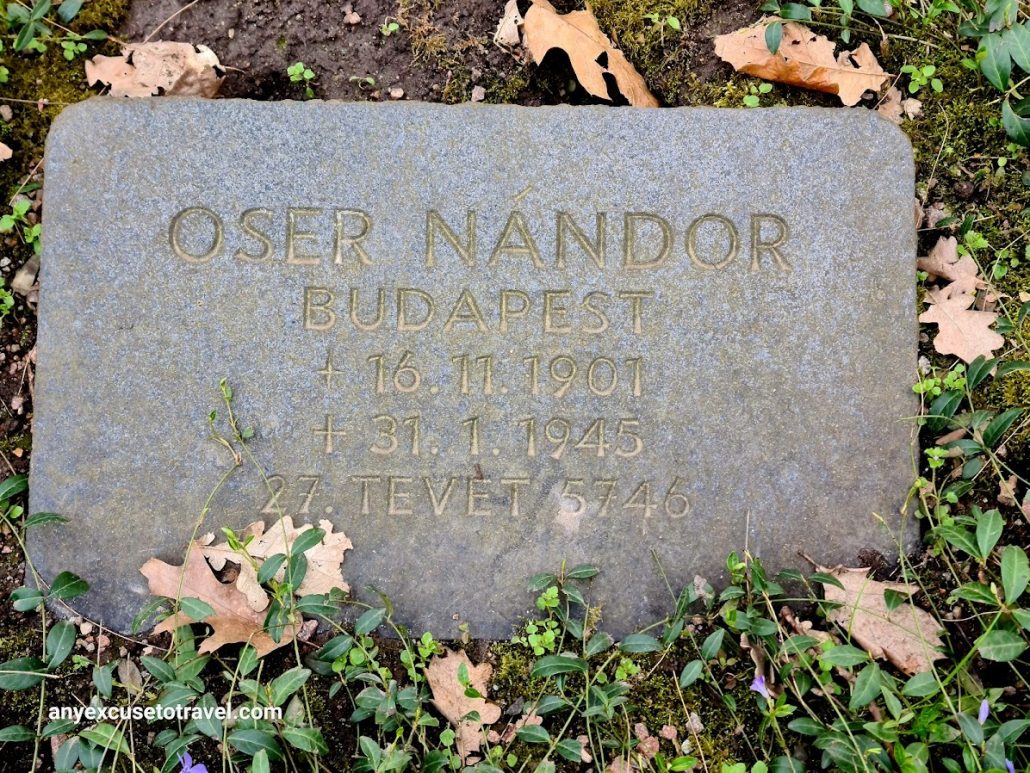

I stopped for a while when I came across a Hungarian name and saw the memorials of the different nationalities who had died there, some 28 countries were represented in the camp and its subcamps at various times during the Second World War.

Nandor Oser was born on 16 November 1901 in Budapest, where he became a paper manufacturer. He married, and he and his wife Magda had a son. The Oser family suffered under the anti-Jewish laws passed by the Hungarian government in 1938. In March 1944 the German Army invaded Hungary. In November that same year, Nandor was forced on a death march via the city of Vienna to the Concentration Camp Neuengamme near Hamburg. He died there on 31 January 1945. The exact cause of death is not known. Nandor Oser was 43 years old.

Then the penny dropped. I was both relieved and horrified anew: relieved that I’d understood what was amiss and horrified that I was rationalising what I was seeing.

It was a concentration camp – not an extermination camp. Hope vs no hope.

In all, the SS incarcerated approximately 104,000-106,000 people in Neuengamme from December 1938 until May 1945; approximately 13,500 of the prisoners were women. The largest groups by nationality were Soviets (34,350); Poles (16,900), French (11,500), Germans (9,200), Dutch (6,950), Danes (4,800), and Belgians (4,800). Initially, there were very few Jews in the camp; by 1942, they numbered between 300 and 500. In the summer and autumn of 1942, the SS removed all of the Jews, deporting those not killed in the camp to Auschwitz. In 1944, the SS transferred both Polish and Hungarian Jews to Neuengamme, many of them via Auschwitz. In all, some 13,000 Jews were prisoners in Neuengamme.

The Holocaust Explained tells me that a concentration camp is ‘a place where people are concentrated and imprisoned, usually without trial. Inmates are usually exploited for their labour and kept under harsh conditions, though this is not always the case.’ It was the case in Neuengamme, though. Labour detachments were sent, for example, to Hamburg and Bremen to clean the streets of rubble following Allied bombings. Prisoners were not allowed in the bomb shelters and some died a marginally better death – a sudden death in the streets of Germany.

Extermination camps were another beast entirely – they were set up to ‘murder and annihilate all races deemed degenerate, primarily Jews, but also Roma.’

Prisoners entering the camp were showered and shaved of all body hair. They swapped their clothes for the striped uniform of the camp, emblazoned with a nationality letter on a triangle. For example, prisoners arriving from the Netherlands wore an H. Their numbers were not tattooed on their skin but on their clothes.

Conditions were harsh. Food was far from plentiful. Hygiene was but wishful thinking. In December 1941, a ‘louse-born typhus epidemic’ claimed 1000 lives. Beatings and abuse were common. Soon, the heat and the work turned muscled men into muselmen: slang to describe those suffering from starvation and exhaustion. Those who died were cremated in Hamburg until the spring of 1942 when Neuengamme built its own crematorium. It was then, too, that the SS began killing off those too weak to work. The chosen from Neuengamme were sent to a euthanasia site in Bernberg an de Saale to be killed in gas chambers. From 1943, Neuengamme murdered its own… by lethal injection.

Concentration camps, like extermination camps, provided ample fodder for medical experiments. Neuengamme was no exception. In 1944, Kurt Heissmayer, an SS doctor, experimented on 20 Jewish children brought in from Auschwitz. The following year, on 20 April, the children were murdered in the Bullenhuser Damm School in Hamburg to cover up the crime.

In the winter of 1944-1945, Dr. Ludwig-Werner Haase tested a new water filter by adding 100 times the safe dose of arsenic to water. He then filtered the water using the new machine, and gave it to more than 150 prisoners over a 13-day period.

What horrors we are capable of.

In April 1945, when news of the Allies approaching reached the camp, those in charge got everyone ready to leave. They left on box carts or on foot, destination Lübeck. If they fell by the roadside, they were shot. In Lübeck, they were put on three ships – the Athen, the Cap Arcona, and the Thielbeck.

On 3 May, English Typhoon fighters attacked all three ships, unaware of the true nature of their cargo.

The Thielbeck caught fire immediately and capsized within 15 minutes. The Cap Arcona kept burning for days to follow. Of the prisoners that had had the chance to jump ship into the freezing water, many drowned. Those that tried to climb ashore were immediately shot by armed guards. During this catastrophe some 7000 prisoners died. Only a handful survived the calamity. Many have been buried in mass graves in the area. Months after the disaster bodies still washed ashore on the beaches of the Bight of Lübeck.

May 2023 marks the 78th anniversary of the liberation of Neuengamme. I read with interest that talks will be given by sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters of former inmates from the Netherlands and Ukraine. More telling still on 5 May at 2 pm, there will be a Conversation Café with those who have lived to tell the tale.

Five survivors – Dita Kraus, Livia Fränkel, Natan Grossmann, Elisabeth Masur-Kishinowski and Barbara Piotrowska – will travel to Hamburg from different countries to commemorate their liberation 78 years ago with their families. What have their lives been like since the liberation? What is their message to younger generations? At the conversation café, you can personally ask them these and many other questions. Young people from Hamburg prepared the project and will moderate the conversations.

And another that I would definitely go listen to were I there:

Livia Fränkel and Elisabeth Masur-Kischinowski from Stockholm share a similar fate. Both women were deported as teenagers with their Jewish families from Hungary and Czechoslovakia, respectively, and survived various ghettos, the Auschwitz extermination camp, and women’s satellite camps of the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg before being liberated from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Their parents did not survive. We will talk to both of them about the time of their persecution, their life after surviving the Holocaust, the passing on of memories in their families and their commitment against forgetting until today.

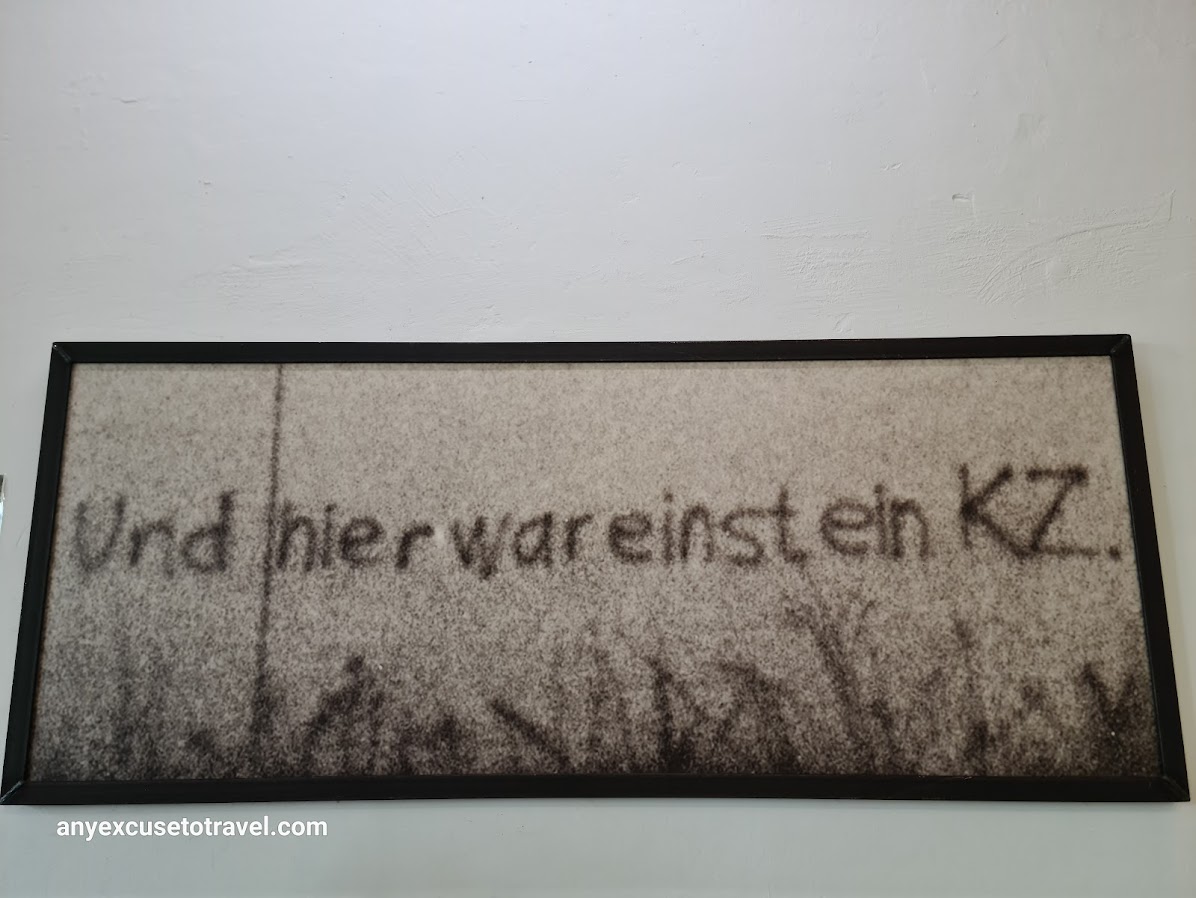

With the war over, the site was destined to remain a prison. First, it was used for three years by the British as an internment camp. Then, in 1948, the city of Hamburg established two prisons there. They remained in operation until 2003 and 2006.

Today, Neuengamme is an exhibition hall, a commemorative garden, and a museum. A place where we can attempt to understand our past in the hope that we won’t allow the same to happen in the future. If you’re visiting Hamburg, make the time. Visit. Read. Learn. And if you come away upset and discomfited, it’s a small price to pay. What was it Socrates said: The unexamined life is not worth living?

Some lines from a Rod McKuen poem also come to mind:

It’s nice sometimes

to open up the heart a little

and let some hurt come in.

It proves you’re still alive.If nothing else

it says to you–

clear as a high hill air,

uncomfortable

as diving through cold water–I’m here.

However wretchedly I feel,

I feel.

If you’ve skipped over the hyperlinks, I understand. We’re short on time and attention. I’m happy that you’ve read this far.

But please, consider taking the time to read Dr Juilette Desplat’s post on the camp and the speech that Barbara Pitorowska gave on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Ravensbrück.

And share them.

Please share them.

We cannot forget. Or rationalise. Or become inured.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

8 responses

I am reading, for the second time, The Escape Artist by Jonathan Freedland – chilling and graphic about the mundanity of how millions were murdered so savagely, and how ‘normalised’ it all was. We should never forget, and yet the collective memory is fading… every reminder is important.

Will put it on my list… thanks

I visited the Holocaust exhibition in Jerusalm ………..there were lots of photographs and exhibits that we have seen before……..but this was the first exhibition/museum where I learnt of Jewish resistance…..the Jews did not all go meekly, some flight and took as many of the Germans (for it was the Germans not just the SS or Gestapo or Nazis who were involved in some way) with them as they could. Good for them! The depressing thing was to realise that sections of each occupied European country were involved………when Jews returned ‘ home’ their houses and flats had been permanently occupied by their neighbours……probably the same neighbours who had given them away. Can we honestly say that if out countries had been occupied we would have acted differently. Yes we must never forget.

I

Have you watched Transatlantic? A fascinating story of resistance…

I’ve often wondered how I’d have fared, what I’d have done. I’d like to think I’d have helped but doubt I’d have been brave enough.

Absolutely heart-rending. The ocean that separates us from these places can make this feel far from our experience. As you remind us, shockingly, this is what humans did to other humans. Thank you for this wonderfully written piece.

Thanks for reading, Dee, and for taking the time to comment