For someone so attached to old stuff, I’m enjoying whatever detour it is that I’m on. I’m a huge fan of tradition and have, on many occasions, eschewed modern architecture in favour of buildings I know have stood the test of time. Bordeaux changed my mind. Milan confirmed it.

The CityLife project is quite something. Covering 366,000 sqm it has everything – retail, residential, office, parks, pedestrian areas, and entertainment – right in the city. The three office towers, designed by Zaha Hadid (Generali), Arata Isozaki (Alliance), and Daniel Libeskind (PWC, he also did the Grand Canal Theatre in Dublin), have added an interesting addition to the city’s skyscape.

Of the three, Hadid’s tower is the most intriguing and not surprisingly, it’s earned itself the nickname Storto (crooked). When she died, too young, in 2016, The Guardian christened her Queen of the Curve. Michael Kimmelman, writing in the New York Times, said she liberated architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity. The first woman to win the Pritzker prize and the first to win the RIBA gold medal, she was some woman for one woman.

Isozaki’s tower has a nickname, too. Il Dritto (the straight one). At 209 metres (259 if you add the broadcast tower) it’s the tallest building in Italy. It has 50 floors! A dizzying height.

The project is built on the grounds of the old market area of Milan. The shopping centre is remarkable in that the shops are downstairs and at ground level, you have the bars and restaurants. We walked through on a Wednesday afternoon and the tables were full of students studying. With its bamboo floors and ceilings, this, the biggest shopping mall in Italy, is a lovely, bright, airy space that didn’t zap my energy as shopping malls normally do. Which is dangerous. I could spend time there.

The residential blocks impart a sense of movement. Designed by Hadid and Libeskind, they ooze modernity … and money. The whole effect is one of consideration. Consideration of modern living requirements. Consideration of the natural environment. Consideration of people’s space.

As we walked towards the Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie (home of DaVinci’s Last Supper), we crossed over from old to new. From modern to traditional. From the 2020s to the early 1900s. The old houses close to CityLife have had their views (and light) blocked somewhat but as you move further away, the light comes in again. It truly is a lovely part of the city.

Although we were heading towards the Last Supper, I’d already decided NOT to go see it. I wanted himself to be there. We did visit the church though and I had my three wishes. The Dominican convent and its courtyards are impressive examples of Renaissance architecture. The church itself dates to the mid-1400s. If you’re in Milan in January, visit the St John the Baptist chapel to see the nativity which opens Christmas night and runs to the end of January.

Across the road, I spotted a sign for a vineyard. Leonardo’s vineyard. A vineyard in the heart of Milan couldn’t be walked by. When Leonardo moved to Milan in 1482 to paint The Last Supper in the Basilica’s refectory, the Duke

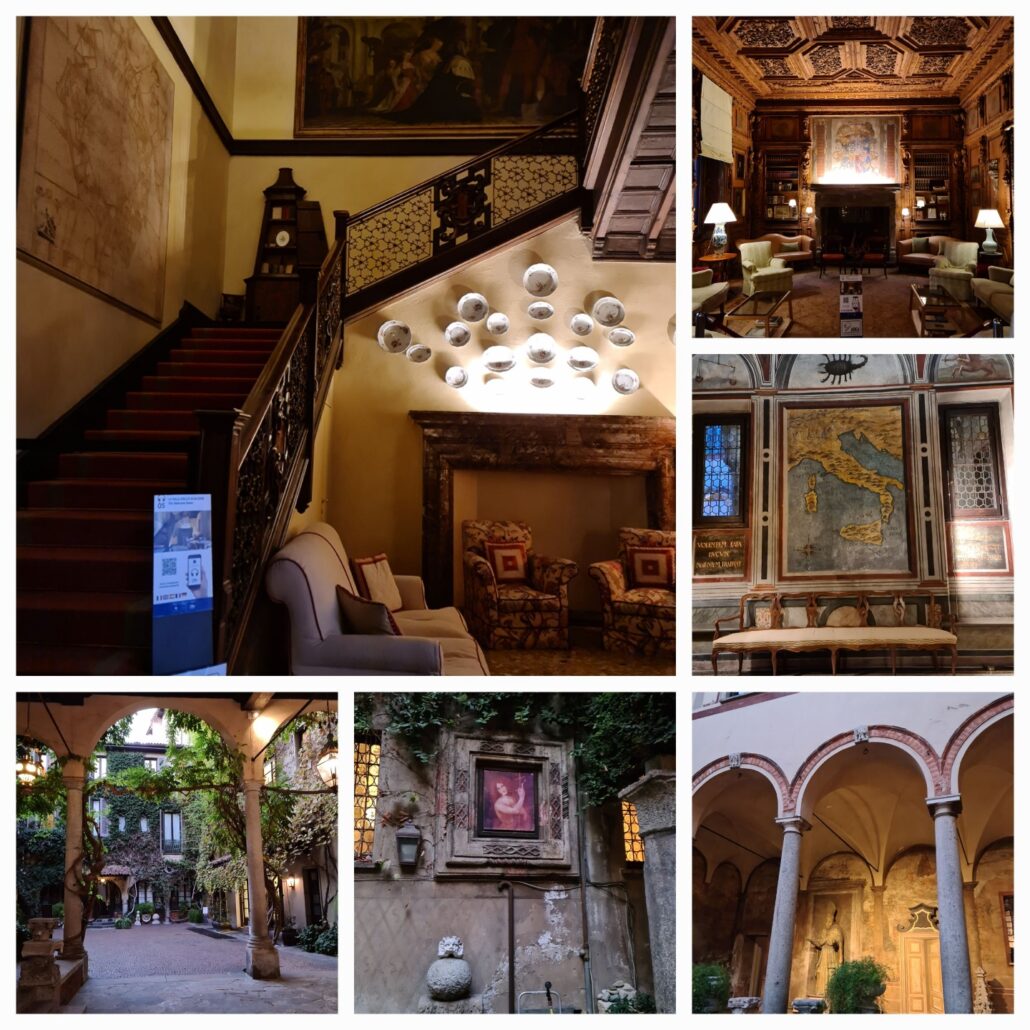

… grants Leonardo the ownership of a vineyard of about 16 rows, planted and cultivated in the field at the bottom of the garden of the Atellani House, the last house standing from 1490 of a hamlet created by the Duke.

It was a most unexpected find. The detail on the walls, the iron air vents, the statues, and the fountains, are all rather splendid. Any sort of reconstruction work in Italy is bound to unearth statutes or pillars or bits of earthenware. They’re kept, lining inner courtyards, or as was done here, mounted on walls. Old is everywhere. Back in 2007, the ‘living biological residues’ of the original vineyard were unearthed and replanted. In 2018, the grapes were harvested and today, the first 330 bottles are settled in the museum.

There’s a wonderful neighbourhood feel to it all. We ventured onto Piazza Riccardo Wagner and its colourful market, which dates back to 1929. Everything looked so healthy. And fresh. And clean. I had little trouble imagining a lotto win and living locally. Despite my newfound interest in modern architecture, I think had I my druthers, I’d still go for an apartment in one of the old palaces. I don’t think I’m ready to go mod. Not yet.

DaVinci. Wagner. And next Verdi. And Casa Verdi.

Using his own fortune, Verdi built the retirement home for opera singers and musicians, a neo-Gothic structure that opened in 1899. The composer died less than two years later, but he made sure the profits from his music copyrights kept the home running until the early 1960s, when they expired. Today guests pay a portion of their monthly pension to cover basic costs – food and lodging — while the rest comes from donations.

What a lovely idea. I didn’t do my homework though. If I had, I’d have known that both Verdi and his wife are buried here (like Stravinsky and his wife on San Michelle). That’s a grave I’d like to have dropped by.

It was, I think, my third visit to Milan. I was only passing through. Previous trips had taken me to Chinatown, the street markets, the impressive Cimiterio Monumentale, the Cathedral, and a host of other churches. Then, as of now, I was ably guided by the inimitable ES. I’ll introduce you to her properly in a later post. If you’re into Italy she’s someone you should get to know.

I don’t think Milan gets the recognition it deserves. In the global tourist psyche, it lags Venice, Florence, and Rome. But it’s getting there. It’s getting noticed. And it’s well worth a visit.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

One Response