The desert never fails to conjure up images of Western movies. I expect to see Indians in full battle regalia on horseback on each ridge, and spot the dust plume kicked up by cowboys, with lariats on their saddles and spurs on their boots. There’s an other worldliness to it all that defies explanation. The Casa Grande Ruins National Monument in Coolidge AZ has been a part of such a landscape for the last 650 years. It’s one of the largest standing prehistoric structures in North America and a window to a time when primative irrigation systems fed the land and crops that sustained the desert peoples for over a thousand years until about 1450 C.E. It was first mentioned in written form when Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino stumbled across the ruins in 1694 – he dubbed it Casa Grande (great house). Its purpose remains unknown. It could well have been a meeting place for the Sonoran Desert People or an administrative point for the irrigation canals and trade routes. Others say that

Casa Grande functioned partly as an astronomical observatory since the four walls face the points of the compass, and some of the windows are aligned to the positions of the sun and moon at specific times.

But no one really knows.

With the arrival of the railway and the advent of tourism, visitors to the Casa Grande Ruins helped themselves to souvenirs and left their mark in the form of graffiti. Yes, even back then, taggers were busy. Those with an appreciation for its ancient history became concerned.

In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison set aside one square mile of Arizona Territory surrounding the Casa Grande Ruins as the first prehistoric and cultural reserve established in the United States.

Later, in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson declared Casa Grande Ruins a National Monument, the fifth in the country, and the National Park Service became its new custodians.

When you think of the tools they had on hand, that such a place was built and is still standing is quite remarkable. The rafters were made from the ribs of the native Saguaro cactus and threaded through holes high up on the walls of buildings. The mind boggles.

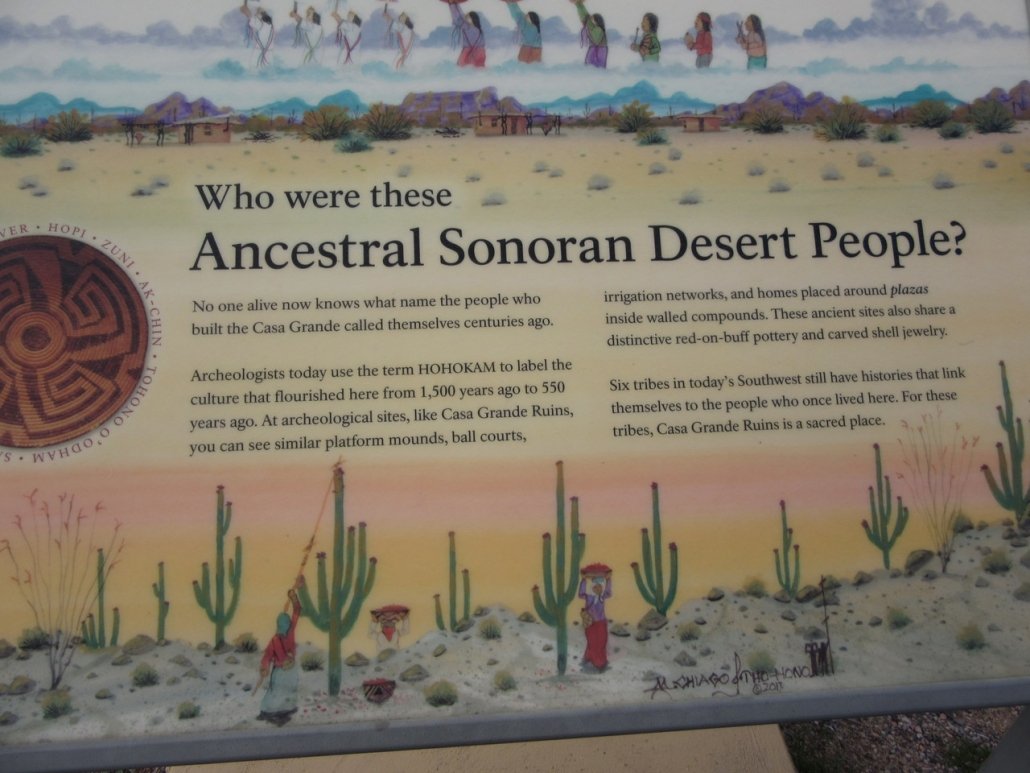

Walking around the Casa Grande Ruins got me thinking about names. The Tohono O’odham are descended from the Hohokam people, the ‘master dwellers of the desert’, who created ‘sophisticated canal systems to irrigate their crops of cotton, tobacco, corn, beans, and squash’. But are they Indian, Native American, or American Indian? Or does it matter? Should I not be bothered?

A 1995 Census Bureau survey that asked indigenous Americans their preferences for names (the last such survey done by the bureau) found that 49 percent preferred the term Indian, 37 percent Native American, and 3.6 percent “some other name.” About 5 percent expressed no preference.

Lakota activist and a founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM), Russell Means, hates the term Native American. In an essay – I am an American Indian, not a Native American – he notes:

At an international conference of Indians from the Americas held in Geneva, Switzerland, at the United Nations in 1977 we unanimously decided we would go under the term American Indian. “We were enslaved as American Indians, we were colonized as American Indians, and we will gain our freedom as American Indians and then we can call ourselves anything we damn please.”

Interestingly, it’s the art appraisers who seem to be fixated on getting it right. The Antiques Roadshow and The Art of Estates are wondering if they’re dealing in Native American art or American Indian art? It would appear that political correctness is of concern.

That said, most of the signs I’ve seen while in Arizona, signs advertising pow-wows and seed farms, all say Native American, so you have to wonder. I like Denis Gaffney’s [(PBS) take:

The term you choose to use (as an Indian or non-Indian) is your own personal choice. … Very few Indians that I know care either way. The recommended method is to refer to a person by their tribe, if that information is known. Native peoples of North America are incredibly diverse. It would be like referring to both a Romanian and an Irishman as European. It’s true that they are both from Europe, but their people have very different histories, cultures, and languages. The same is true of Indians. The Cherokee are vastly different from the Lakota, the Dine, the Kiowa, and the Cree, but they are all labeled Native American. So whenever possible an Indian would prefer to be called a Cherokee or a Lakota or whichever tribe they belong to. This shows respect because not only are the terms Indian, American Indian, and Native American an over simplification of a diverse ethnicity, but you also show that you listened when they told what tribe they belonged to. … What matters in the long run is not which term is used but the intention with which it is used.

Additional reading

American Indian or Native American

I am an American Indian, not a Native American

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

One Response